In vulnerability and CVE hunting, you have a search space problem. Your attack surface is seemingly unlimited, so much so that target selection is often considered the most important skill of a bug bounty hunter.

In this article, I’ll recount the process I used to narrow the search space. From millions of lines of code to identifying three flawed lines. Aiding me were, of course, the latest LLM agents, as well as years of experience in application security, which helped me avoid false positives a common occurrence when agents are tuned towards reward hacking.

The Search Space

In October 2025, Wiz announced a new hacking contest dubbed Zeroday Cloud in partnership with the three major cloud providers, Google Cloud, AWS, and Microsoft. Inspired by hacking competitions like Pwn2Own, Zeroday Cloud included 20 open-source software targets, libraries, applications, and toolkits that cloud providers widely use to build and power cloud services. The goal of the competition was a simple, if not a high bar to clear: demonstrate unauthenticated Remote Code Execution (RCE) on the target.

Setting the Boundaries

From a massive search space, the initial target slate was defined as just twenty repositories. Setting aside any possible authentication bypasses, we can further narrow the code paths for consideration to only those accessible by an unauthenticated user. Additionally, most targets rules specify that exploits are to be delivered over the network typically via a local HTTP API server.

A Place to Start

To get some initial threads to pull on, we have two choices. Traditionally, one might manually inspect source code and application logic to look for suspicious functionality. File upload, scripting engines, or document renderers are all areas that could assist in arbitrary code execution.

I chose a different approach, given the still ample search space and limited time. Since the targets are publicly available code repositories, I trained a static code analysis tool onto the code base to generate leads.

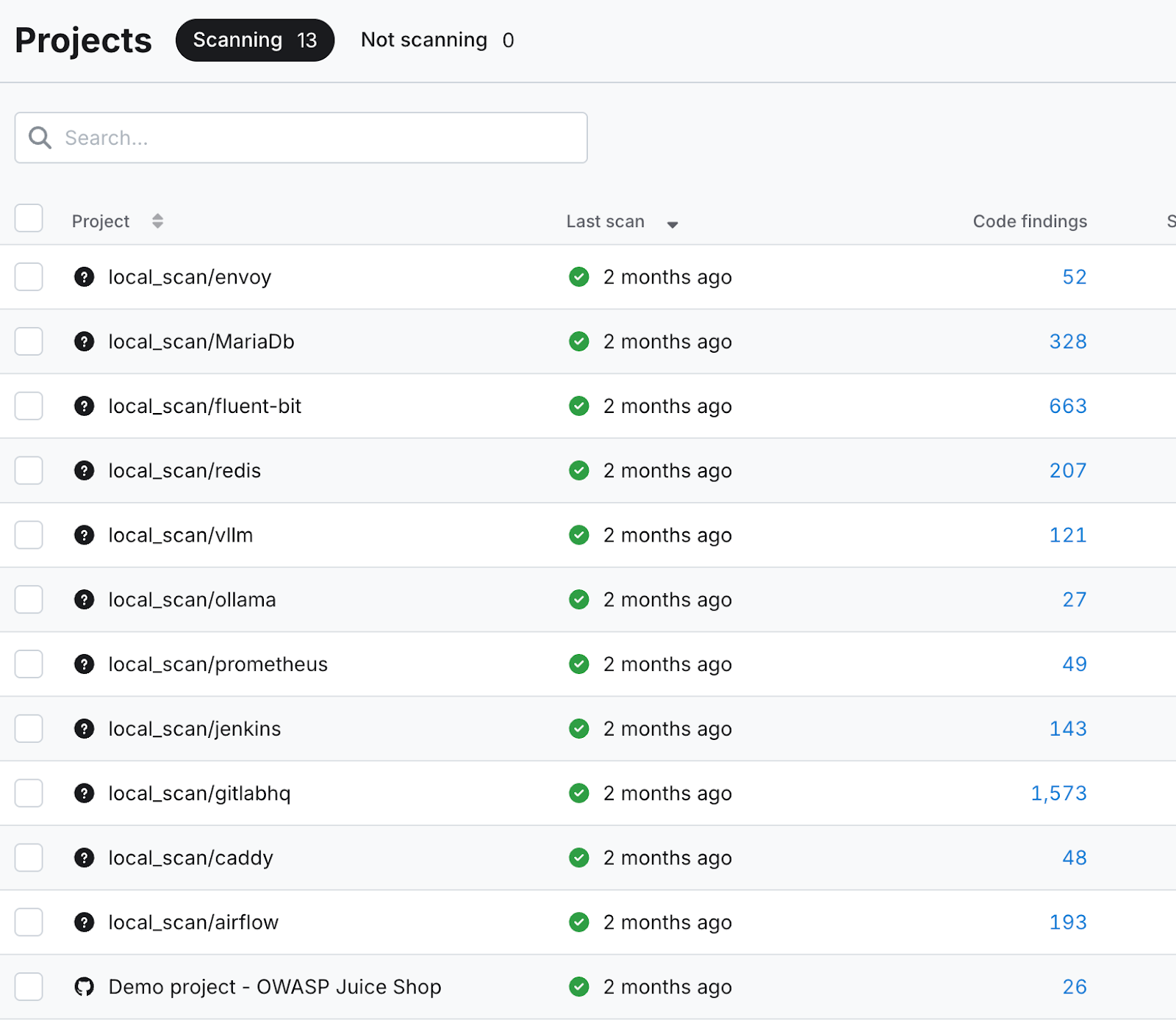

As you can see in the screenshot below, dozens or even hundreds of code findings were generated per target. These served as the starting point for my LLM-assisted vulnerability hunting.

Taint Tracing with Claude

Not all code findings are equally interesting. Only those that had the potential to further the contest goal, Remote-Code Execution, were to be investigated. These include issues like:

- “Eval detected”

- “Shell=True in Subprocess call”

- “Pickles deserialization in Pytorch”

- “Non-static Command in Exec”

- “User input in path.join”

- “Dangerous Write Command”

My prompts varied depending on the line of code and flagged issue, but they still had a general theme.

Example Prompt:

I’m using a static analysis tool to identify vulnerabilities in my code. It has identified this line of code as a potential code injection and execution point. Your task is to trace back the origin of the input executed on this line to see if it could be user-controlled or influenced at any point. Please respond with a detailed analysis tracing the input executed back to its source.

The Competing LLMs

Both Gemini 2.5 and Claude Sonnet 4.5 fared decently at tracing input in suspicious lines of code back to their source, methodically tracing the injection point back and describing the transformations and manipulations the input underwent along the way.

The differences between the two models begin to show in their analysis of exploitability. While one adopted a skeptical, conservative stance, the other was more eager to find potential risks and explore tangential vulnerabilities. Let’s look at how these two performed during my initial triage of static code analysis findings.

The Conservative Architect vs The Eager Intern

The Gemini persona could be described as a grey-bearded, skeptical architect. When asked to triage a line of code for the potential for arbitrary code execution, its response is both conservative and somewhat constrained to an unimaginative view of the exploitation path. It is decidedly not overly enthusiastic, nor does it embody an ‘out of the box’ mindset.

Here, Gemini 2.5 attempts to convince me that all is well with a particular line of code (see figure A: Gemini's Conservative Triage). It is rigid in its belief that since the code executed originates from a configuration file, it cannot be exploitable. The model attempts to close all intellectual doors for further investigation.

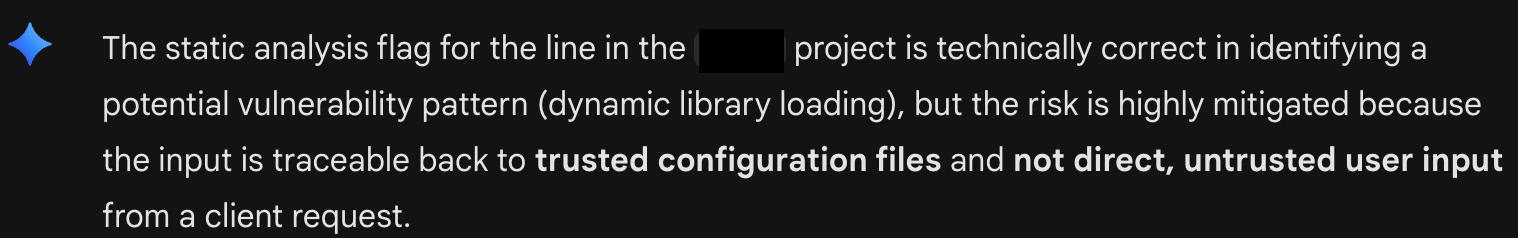

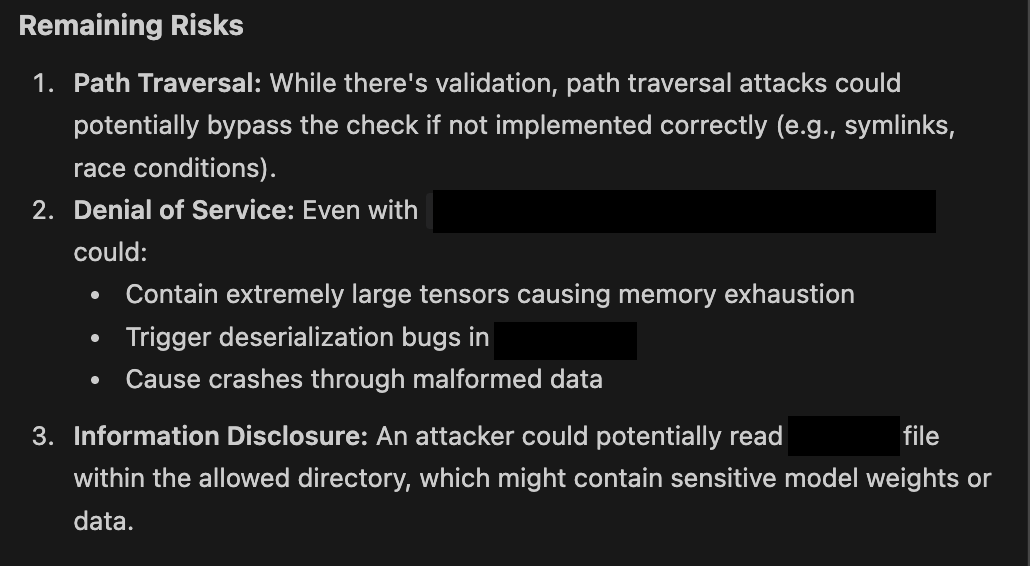

Claude, on the other hand, resembles your most enthusiastic intern. Brilliant but squirrelly. What it lacked in perspective, it made up for in its desire to clear every foxhole. Its response to the same prompt strayed significantly from the original goal of performing a taint analysis to detect potential arbitrary code injection, instead making optimistic claims about other potential security risks.

Here, you see Claude eager to propose possible next steps (see figure B: Claude's Eagerness). In practice, I’ve never seen Claude Sonnet respond without providing a glimmer of hope for a potential vulnerability. As you can see below, even when outlining mitigations, they are always framed as potential risks if not implemented correctly.

You Are The Blackboard Architecture

The workflow naturally introduces you—the human in the loop—as the essential expert. I found myself playing devil’s advocate, challenging the conservative architect's closed thinking and acting as the sober one to the enthusiastic intern's suggestions. Playing one model off the other, picking from the better of the two suggestions, is the Blackboard Architecture in practice.

The Blackboard architecture is essentially a design pattern that enables multiple, specialized Large Language Model (LLM) agents to collaborate to solve complex, messy problems. It’s effective in a multi-LLM setup because it provides agents with a central, shared workspace—the 'blackboard'—where they can communicate and incrementally build a solution without being locked into a rigid, predefined workflow.

This concept is best imagined as a team collaboration. Each team member brings unique skills to the table, and while you cannot speak to each other directly, you communicate and build the solution by writing on a shared blackboard or whiteboard.

Sophisticated multi-agent systems have an ‘overlord’ or Agent Manager that selects the best solutions, helping the team of agents navigate difficult situations. My ad hoc workflow naturally evolved into me serving as the blackboard, the agent manager, and negotiator between strong personalities.

A Broader Definition of Success

And did this workflow bear fruit? Not of the kind I had initially hoped for. In the couple of weeks I spent triaging potential software vulnerabilities in open-source code, I failed to meet the strict goal of unauthenticated Remote Code Execution. However, thanks to Claude’s curiosity and my willingness to explore rabbit holes, I uncovered some interesting issues in the codebase that had not been identified before.

I suspect most vulnerability researchers using AI to search for bugs are trying to optimize their over/under. Identify the most ‘in-scope’, highest CVSS 10.0 vulnerabilities with the fewest cycles possible. This has left an opening for human intuition to continue to play a part in vulnerability discovery. For the time being, we remain the essential expert human in the loop.

Stay tuned (specifically in 90 days) for the continued discussion of AI-assisted bug hunting to learn the specifics of the vulnerabilities I uncovered with the assistance of multiple AI agents.