The vulnerability surfaced just days before Christmas and, in the worst case, allowed unauthenticated attackers to read server memory remotely. Fixes are already available, but the blast radius is large: the issue affects virtually every MongoDB release going back nearly ten years.

Dubbed MongoBleed (CVE-2025-14847), the flaw is a pre-authentication vulnerability in the MongoDB Server. It stems from mismatched length fields in zlib-compressed protocol headers, which can cause the server to return uninitialized heap memory to an unauthenticated client. Put plainly: if an attacker can reach a MongoDB instance over the network, they can attempt to “bleed” memory contents without ever logging in.

MongoDB’s own issue tracker is explicit about remediation, urging users to upgrade to fixed releases across all supported branches (8.2.3, 8.0.17, 7.0.28, 6.0.27, 5.0.32, or 4.4.30).

What makes MongoBleed particularly concerning is how accessible exploitation is. A public proof-of-concept is already available and requires little more than the IP address of a reachable MongoDB server. From there, attackers can trawl leaked memory for high-value secrets — including database credentials stored in plaintext, cloud access keys, and other sensitive material. The exploit is purpose-built to hunt for exactly these kinds of secrets, dramatically lowering the bar for real-world abuse.

Finding MongoDB Everywhere: Using Vectra to Identify Exposure, Lateral Risk, and Exploitation

Before you can worry about exploitation, you need to answer a much more basic question:

Where is MongoDB actually running in my environment?

That sounds trivial. It isn’t.

Between legacy applications, shadow IT, cloud experiments, containerized workloads, and “temporary” databases that somehow became permanent, MongoDB has a habit of popping up in places no one remembers owning. According to Shodan, more than 200,000 MongoDB instances are currently exposed to the internet. That’s just the visible part of the iceberg.

The more interesting (and more dangerous) question is what’s happening inside your network:

- MongoDB instances reachable by any compromised host

- Databases bound to non-standard ports

- Services running without authentication assumptions

- Internal databases that become perfect stepping stones for lateral movement or privilege escalation

This is where network-level visibility matters — and where the Vectra platform shines.

With Vectra’s deep network visibility and enriched metadata, we already have the raw material needed to hunt for MongoDB anywhere, regardless of port, protocol, or deployment model. And when metadata isn’t enough, Vectra Match (Suricata) lets us go one step further with protocol-aware signatures.

Let’s break this down.

1. Characteristics of a MongoDB Instance on the Network

To hunt MongoDB effectively, we need to understand how it behaves on the wire.

Default Network Characteristics

At a high level, MongoDB is a TCP-based, client-server protocol.

Common characteristics include:

- Default TCP port: 27017

- Common alternate ports: 27018, 27019, or arbitrary high ports in containerized / cloud environments

- Long-lived TCP sessions: clients often keep connections open

- Bidirectional request/response traffic: not just short bursts

But port-based detection alone is fragile — attackers and admins both know that.

MongoDB Wire Protocol (Cleartext)

When TLS is not enabled, MongoDB traffic is fully visible on the wire.

Key traits of the MongoDB wire protocol:

- Binary protocol with a standard message header

- Header fields include:

- Message length

- Request ID

- Response-to ID

- OpCode (e.g., OP_MSG, OP_QUERY, legacy ops)

- Early packets often contain:

- Client handshake (isMaster / hello)

- Driver metadata (language, version)

- Authentication negotiation

From a network perspective, this gives us:

- Clear server responses

- Identifiable protocol structure

- Predictable request patterns during connection setup

In other words: easy to fingerprint, even on non-standard ports.

MongoDB with TLS Enabled

TLS complicates things — but it doesn’t make MongoDB invisible.

When TLS is active:

- Payload is encrypted

- Protocol contents are hidden

- But session behavior and metadata remain

What we still see:

- TCP destination and source

- Port usage (even if non-standard)

- Session duration

- Byte counts and directionality

- Certificate metadata (when available)

- Server Name

- Issuer

- Certificate reuse across hosts

This is critical, because most real-world environments are mixed:

- Some MongoDB instances use TLS

- Others don’t

- Some start in cleartext and upgrade

- Some rely on internal “trusted network” assumptions

Vectra’s metadata makes these differences visible — without decrypting traffic.

Why This Matters for MongoBleed

MongoBleed is a pre-auth, network-reachable vulnerability.

That means:

- Internet-exposed MongoDB = immediate risk

- Internally reachable MongoDB = post-compromise goldmine

- TLS does not remove exploitability

- Authentication does not remove exploitability

If an attacker can connect, they can probe.

2. Hunting MongoDB Instances Using Network Metadata

This is where we move from theory to practice.

Vectra continuously generates enriched network metadata that allows us to hunt MongoDB instances without relying on logs, agents, or asset inventories.

Finding Internet-Exposed MongoDB Instances

Key hunting approaches:

- Identify internal hosts accepting inbound connections from the internet

- Filter on:

- TCP services with server-like behavior

- Long-lived sessions

- Repeated inbound connections from diverse source IPs

- Correlate with:

- Known MongoDB default ports

- High-entropy inbound traffic on unusual ports

- TLS certificates reused across multiple MongoDB listeners

This immediately surfaces:

- Forgotten cloud VMs

- Test databases accidentally exposed

- “Temporary” services that became permanent

And unlike Shodan, this is your actual exposure, not a scan result.

SELECT id.resp_h, resp_hostname.name,

COUNT(*) AS connection_count

FROM network.isession._all

WHERE id.resp_p = 27017

AND local_orig = FALSE

AND local_resp = TRUE

AND timestamp BETWEEN date_add('day', -14, now()) AND now()

GROUP BY id.resp_h, resp_hostname.name

ORDER BY connection_count DESC

LIMIT 100

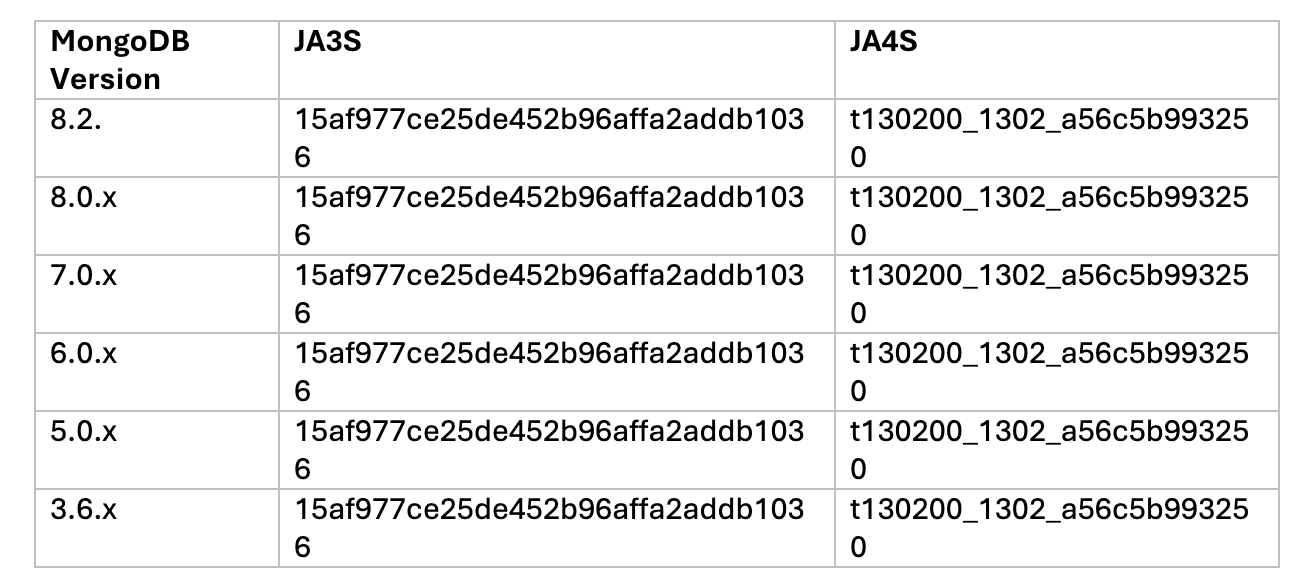

In this scenario, we focus on identifying MongoDB servers running over TLS — regardless of the TCP port in use. Since payload inspection is not possible with encrypted traffic, we rely on TLS fingerprinting, specifically JA3 and JA4, which are automatically computed by the Vectra platform for every observed TLS session and enriched into network metadata.

JA3 and JA4 fingerprint TLS client behavior by hashing characteristics of the TLS handshake, such as supported cipher suites, extensions, and protocol versions. Their server-side counterparts — JA3S and JA4S — capture the fingerprint of the TLS server response, making them particularly useful for identifying server technologies without decrypting traffic.

In practice, this allows us to spot MongoDB TLS servers based on how they negotiate TLS, even when they run on non-standard ports or are otherwise indistinguishable at the transport layer.

It’s important to note, however, that JA3S and JA4S fingerprints are not globally unique. Similar fingerprints can be shared across different server stacks and libraries, which means collisions are possible and context still matters.

That said, testing across multiple MongoDB versions shows that JA3S and JA4S fingerprints are highly consistent between releases, making them a reliable signal when combined with network behavior, session patterns, and endpoint context.

Hunting MongoDB Servers on Non-Standard Ports

Identifying MongoDB servers that are not bound to a well-known port requires additional analysis and context. In these cases, simple port-based filtering is insufficient, and we need to rely on higher-level indicators derived from network metadata.

One effective approach is to examine server-side identifiers, such as the responder’s hostname or the TLS Server Name Indication (SNI), and look for patterns that suggest database infrastructure. Hostnames referencing database roles, clusters, shards, or replica sets can provide strong hints that the service in question is a MongoDB backend — even when it is listening on an unexpected port.

SELECT id.orig_h, id.resp_h, id.resp_p, server_name, cipher, version, ja3s, ja4s, timestamp

FROM network.ssl._all

WHERE (ja3s = '15af977ce25de452b96affa2addb1036' OR ja4s = 't130200_1302_a56c5b993250')

AND local_orig = FALSE

AND local_resp = TRUE

AND timestamp BETWEEN date_add('day', -14, now()) AND now()

ORDER BY timestamp DESC

LIMIT 1000

If we additionally factor in the destination port:

SELECT id.orig_h, id.resp_h, id.resp_p, server_name, cipher, version, ja3s, ja4s, timestamp

FROM network.ssl._all

WHERE (ja3s = '15af977ce25de452b96affa2addb1036' OR ja4s = 't130200_1302_a56c5b993250')

AND id.resp_p = 27017

AND local_orig = FALSE AND local_resp = TRUE

AND timestamp BETWEEN date_add('day', -14, now()) AND now()

ORDER BY timestamp DESC

LIMIT 1000

Note: MongoDB does not ship with default TLS certificates or private keys. When TLS is enabled, administrators must explicitly provide their own certificate and key material. Additionally, MongoDB uses TLS 1.3 by default when TLS is active, which means traditional certificate and x.509 metadata are not exposed in network telemetry.

Finding Internal MongoDB Instances

Internal MongoDB is often more dangerous than external exposure.

Why?

- Attackers don’t need to scan the internet

- Compromised hosts can enumerate freely

- Internal databases often lack hardening

Hunting patterns include:

- East-west TCP services acting as persistent servers

- Repeated connections from application tiers

- Known MongoDB behavioral patterns (session length, request cadence)

- Services reachable by many different internal hosts

This quickly reveals:

- Databases reachable from everywhere

- Flat network design issues

- Ideal lateral movement targets

SELECT

id.resp_h,

resp_hostname.name,

COUNT(*) AS connection_count

FROM network.isession._all

WHERE id.resp_p = 27017

AND local_orig = TRUE

AND local_resp = TRUE

AND timestamp BETWEEN date_add('day', -14, now()) AND now()

GROUP BY id.resp_h, resp_hostname.name

ORDER BY connection_count DESC

LIMIT 100

Also here, we can use JA3S and JA4S:

SELECT id.orig_h, id.resp_h, id.resp_p, server_name, cipher, version, ja3s, ja4s, timestamp

FROM network.ssl._all

WHERE (ja3s = '15af977ce25de452b96affa2addb1036' OR ja4s = 't130200_1302_a56c5b993250')

AND local_orig = TRUE

AND local_resp = TRUE

AND timestamp BETWEEN date_add('day', -14, now())

AND now() ORDER BY timestamp DESC

LIMIT 1000

SELECT id.orig_h, id.resp_h, id.resp_p, server_name, cipher, version, ja3s, ja4s, timestamp

FROM network.ssl._all

WHERE (ja3s = '15af977ce25de452b96affa2addb1036' OR ja4s = 't130200_1302_a56c5b993250')

AND id.resp_p = 27017

AND local_orig = TRUE

AND local_resp = TRUE

AND timestamp BETWEEN date_add('day', -14, now())

AND now()

ORDER BY timestamp DESC

LIMIT 1000

Hunting for Potential MongoBleed Exploitation

Even without payload visibility, exploitation attempts leave footprints.

Things to look for:

- Unusual connection attempts to MongoDB services

- Short-lived, repeated connections from unexpected hosts

- New MongoDB client behavior from systems that never used it before

- Sudden spikes in connections

- MongoDB traffic originating from non-application systems (workstations, jump hosts, compromised servers)

These are classic signs of:

- Reconnaissance

- Exploit testing

- Automated memory probing

Vectra’s entity-centric view makes this stand out quickly — especially when combined with identity and host context.

SELECT

id.orig_h,

id.resp_h,

id.resp_p,

duration,

conn_state,

timestamp,

orig_ip_bytes,

resp_ip_bytes

FROM network.isession._all

WHERE conn_state IN ('SF')

AND duration < 5000

AND orig_ip_bytes = 44

AND first_orig_resp_data_pkt = 'LAAAAAEAAAAAAAAA3AcAAA=='

AND timestamp BETWEEN date_add('day', -14, now())

AND now()

ORDER BY timestamp DESC

LIMIT 100

This query is an example of how to look for unencrypted MongoDB traffic where the first packet has a size of 44 bytes with a MongoDB Header defining a compressed message.

The MongoDB Header format is defined as follows:

struct MsgHeader {

int32 messageLength; // total message size, including this

int32 requestiD; // identifier for this message

int32 responseTo; I/ requestiD from the original request

//_(used in responses from the database)

int32 opCode; //message type

}The PoC that was published uses a length of 44 bytes with an opCode of 2012 (Compressed Data).

3. Going Deeper with Vectra Match (Suricata)

Metadata gets us far. Vectra Match lets us be precise.

Using Suricata-based signatures, we can explicitly identify MongoDB traffic and exploitation patterns. The Vectra Match Ruleset is based upon the Commercial ETPro ruleset and contains the following two rules for MongoBleed. The first is to detect inbound auth attempts and the second is to detect the exploit itself. They are both included in the Vectra Match Curated Ruleset.

Detecting Potential Exploit Usage

For MongoBleed specifically, signatures can target:

- Malformed or abnormal protocol lengths

- Repeated handshake attempts without authentication

- Protocol anomalies consistent with memory disclosure attempts

- High-frequency probing behavior against MongoDB services

This doesn’t rely on CVE-specific payloads alone — it focuses on behavior, which is far harder for attackers to evade.

alert tcp any any -> $HOME_NET 27017 (msg:"ET INFO MongoDB SASL Authentication Detected"; flow:established,to_server; flowbits:set,ET.MongoDB_Auth_Attempt; flowbits:noalert; content:"|dd 07 00 00|"; offset:12; depth:4; content:"saslstart"; fast_pattern; nocase; distance:0; reference:url,www.alienfactory.co.uk/articles/mongodb-scramsha1-over-sasl; classtype:misc-activity; sid:2066500; rev:1; metadata:affected_product MongoDB, attack_target Server, created_at 2025_12_29, deployment Perimeter, confidence High, signature_severity Informational, updated_at 2025_12_29; target:dest_ip;)

alert tcp any any -> $HOME_NET 27017 (msg:"ET EXPLOIT MongoDB Unauthenticated Memory Leak (CVE-2025-14847)"; flow:established,to_server; flowbits:isnotset,ET.MongoDB_Auth_Attempt; content:"|dc 07 00 00 dd 07 00 00|"; fast_pattern; offset:12; depth:8; content:"|02|"; distance:4; within:1; threshold:type threshold, track by_src, count 10, seconds 120; reference:url,bigdata.2minutestreaming.com/p/mongobleed-explained-simply; reference:cve,2025-14847; classtype:attempted-admin; sid:2066501; rev:1; metadata:affected_product MongoDB, attack_target Server, created_at 2025_12_29, cve CVE_2025_14847, deployment Perimeter, deployment Internal, confidence Low, signature_severity Major, updated_at 2025_12_29; target:dest_ip;)

Cleartext, TLS, and Non-Standard Ports — Covered

Across all of these hunts, the key takeaway is simple:

- Cleartext MongoDB: protocol + metadata + signatures

- TLS MongoDB: metadata + behavioral analysis + certificates

- Non-standard ports: behavior beats ports every time

Attackers don’t care what port MongoDB runs on — and defenders shouldn’t either.

What to alert on vs. what to hunt

Page the on-call when

- Internet-facing MongoDB has inbound bursts from unknown IPs

- Internal MongoDB servers get “scanner-like” connection storms

- New clients start talking MongoDB protocol on odd ports

Hunt when

- You see MongoDB protocol on non-standard ports (Tier 2)

- You see auth attempts from unusual sources (Tier 3)

- You see a spike in short-lived connections, even without payload visibility (Level 2)

Mitigation (because detection is not a substitute for patching)

MongoDB’s fix guidance is straightforward: upgrade to fixed versions (8.2.3 / 8.0.17 / 7.0.28 / 6.0.27 / 5.0.32 / 4.4.30). (jira.mongodb.org)

NVD summarizes the vulnerability as length-field mismatch in zlib headers allowing unauthenticated heap reads. (NVD)

A public PoC exists, lowering attacker effort. (GitHub)

Why This Matters?

MongoBleed is just the latest reminder that databases are not passive infrastructure. They are active attack surfaces.

If you can’t answer:

- Where is MongoDB running?

- Who can reach it?

- Who is touching it now?

…then patching alone won’t save you.

The Vectra AI Platform gives you the visibility to answer those questions — and the hunting and detection capability to act before “bleeding memory” turns into a full-scale breach.

Want to learn more? Join us for the upcoming Attack Lab session where we will break down how MongoBleed works and how to rapidly hunt and validate risks within MongoDB: LINK TO REG PAGE