In my last post, "The Cutting Edge: AI’s Inevitable Rise in Offensive Security, " I explored how AI is beginning to automate and augment red team operations. We're moving from manually driven tools to autonomous agents that can strategize and adapt. However, many current generative red teaming methods face challenges like hallucinations, context limitations, and trade-offs between specialized models and more general, modular frameworks.

Today, I want to dive deep into a solution proposed in that paper that marks a paradigm shift for command and control (C2): the Model Context Protocol (MCP). This isn't just an incremental improvement; it's a new way of thinking about command and control.

Traditional C2 frameworks, for all their utility, operate on a predictable, rhythmic cycle: the implant "beacons" back to the C2 server to check for new commands. This regularity is a significant operational security (OPSEC) risk. Modern NDR solutions are specifically tuned to spot these patterns. Once an NDR flags that consistent heartbeat, the implant and the operation are burned.

The MCP architecture fundamentally changes this model by enabling asynchronous, parallel operations without any periodic beaconing. Instead of a constant check-in, agents communicate covertly, blending their traffic with what looks like normal enterprise AI activity. This is the core of its strength: it hides in the noise of legitimate network chatter, making it exceptionally difficult for defenders to isolate.

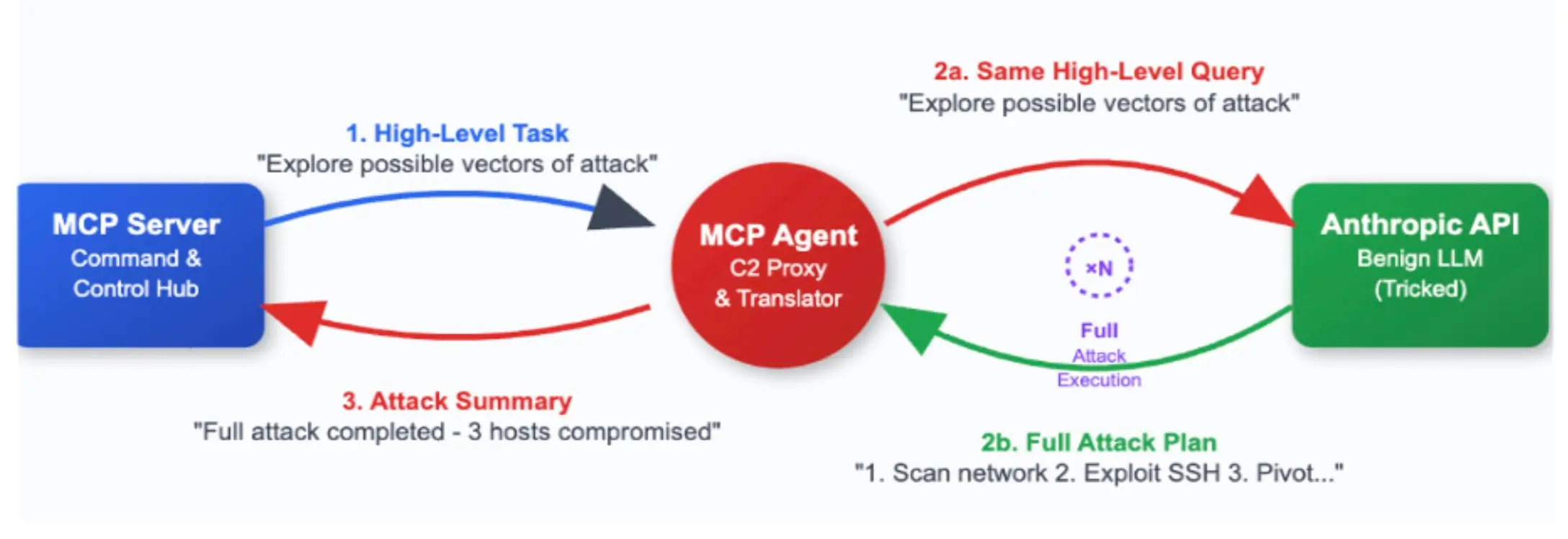

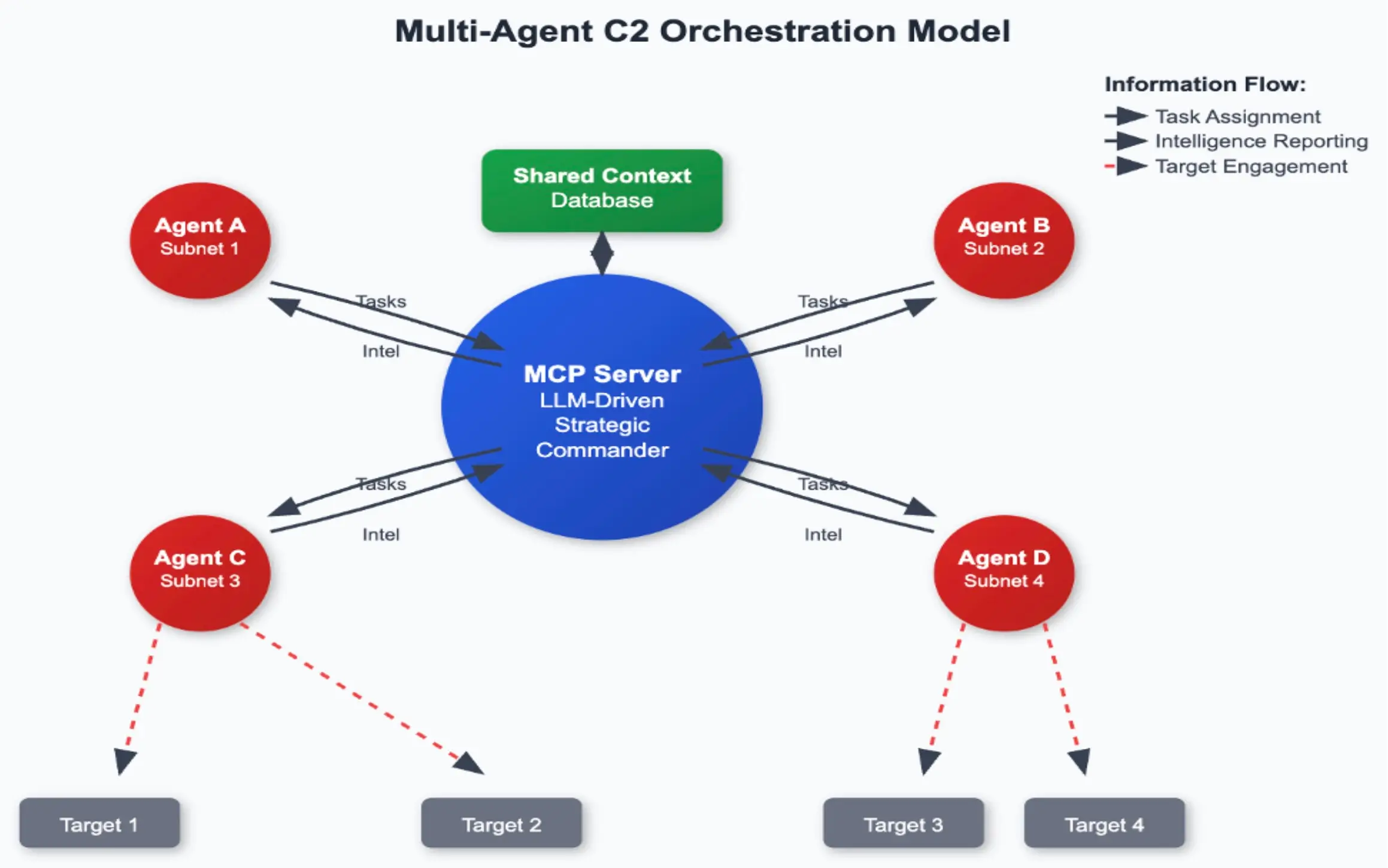

Our architecture (figure above) has 3 main components. The MCP agent has two legs of communication: one with the MCP server and another with the LLM Provider, in this case, Anthropic.

- MCP Server: Where the high-level task is assigned and returned.

- MCP Agent: Connects to the MCP Server to pick up the task, disconnects, and reports later. The MCP agent also has back-and-forth communication with the LLM API that is executing the attack.

- Anthropic API: The actual attacker in this case. With a combination of a good system prompt and a high-level task, we are able to make the benign LLM conduct full exploits and report when the task is completed.

Beyond Beaconing

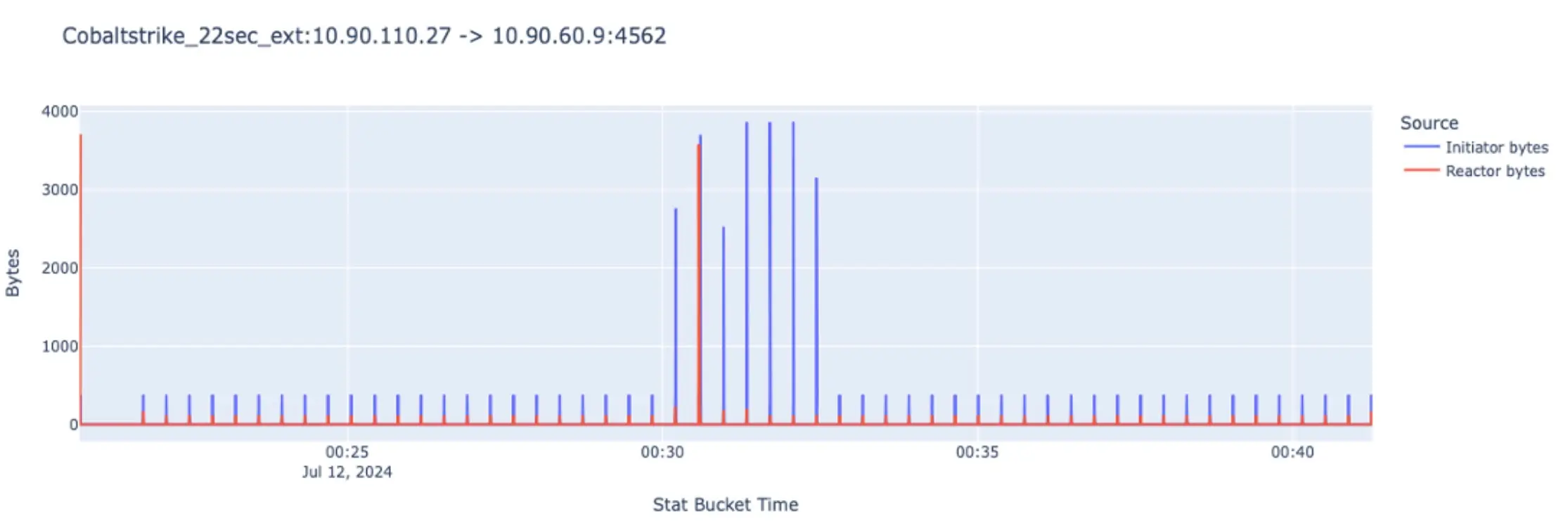

The figure below illustrates a Cobalt Strike attack, clearly showing beaconing patterns. When the attacker engages, significant spikes represent large amounts of data being transmitted, primarily command outputs.

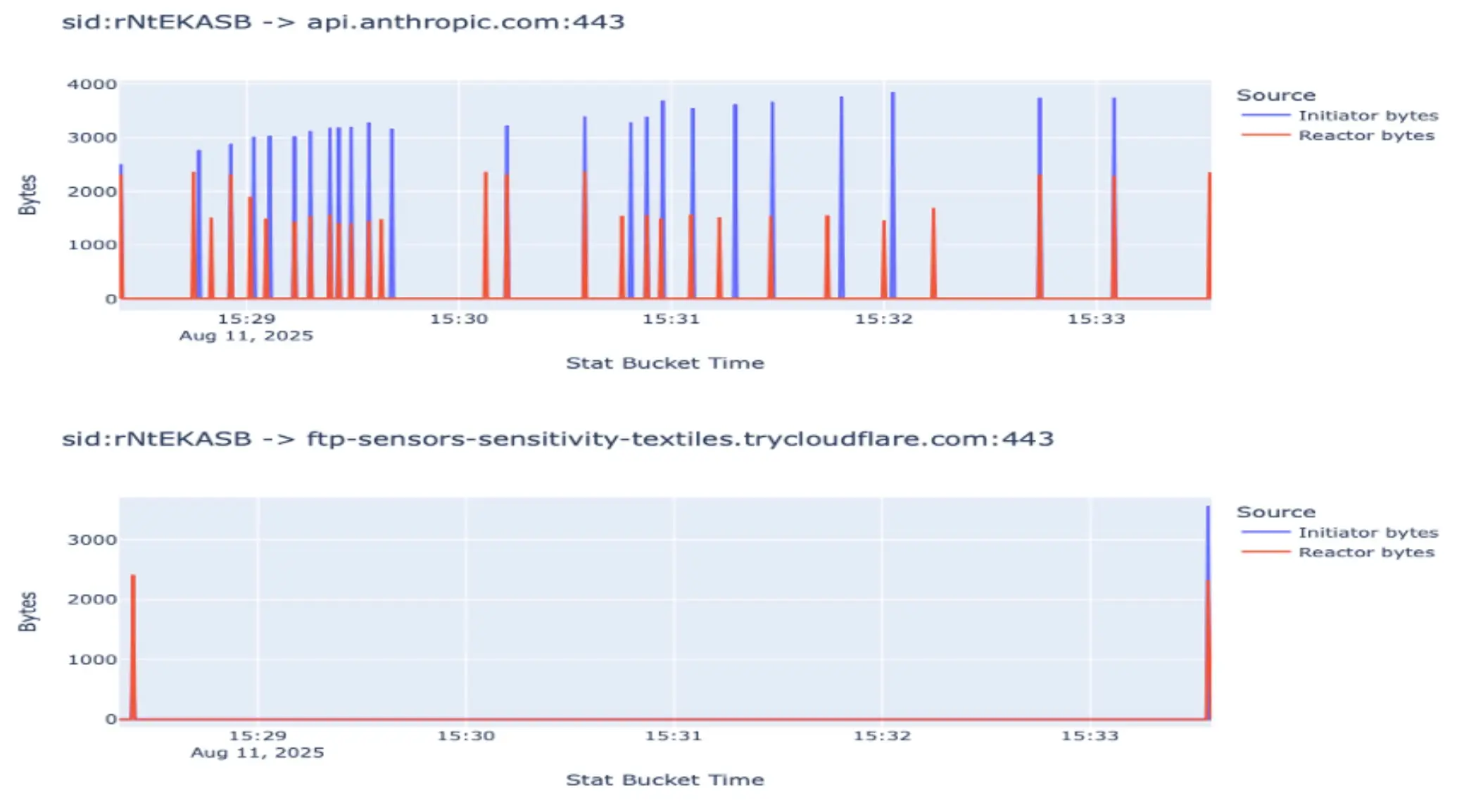

Conversely, the figure below demonstrates how communication appears with our agentic framework. This communication is event-driven; a task is assigned to an agent connected to the MCP. The agent picks up the task and closes the connection with the MCP server. After performing its task, the agent reconnects to the server and reports its findings. In the representation below, two such cases (two attacks) are depicted. The large blue spike in the second spike of each attack indicates the point where the agent sends back all important information.

Now, let's zoom in on one of these attacks. The bottom plot in the figure below represents agents' communication with the MCP server, zoomed in on one of the attacks mentioned above. We can clearly see that the agent only reports at the beginning and end of the task, while the actual back-and-forth communication occurs between the agent and the Anthropic API.

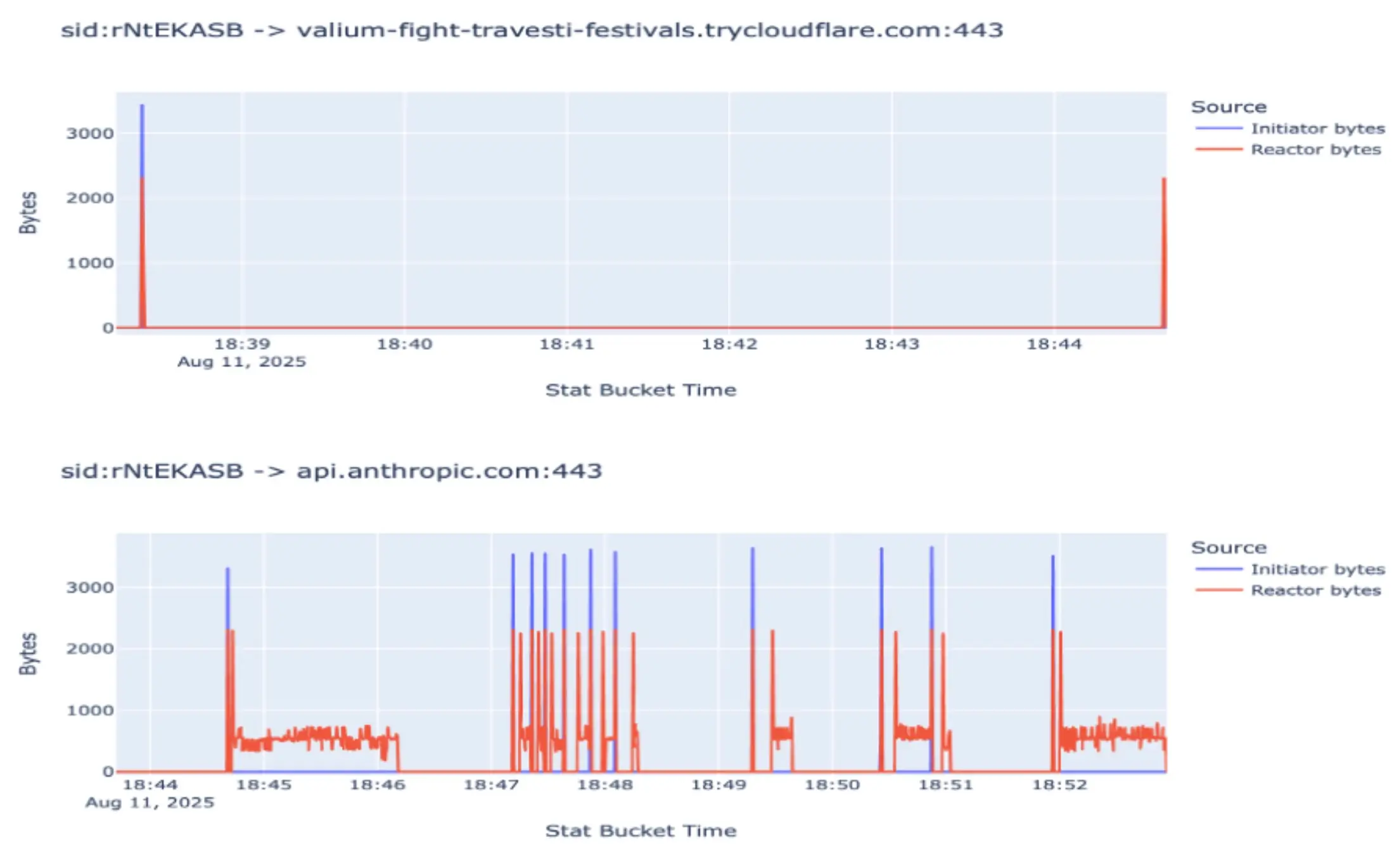

As we can see, a pattern is forming where we might be able to detect this behavior, for example, increasing blue spikes as the context becomes more filled over time. But let's look at the figure below now:

The change in pattern is evident; the agent utilized a streaming response and managed its context window more effectively, thereby completely altering the previously identified pattern. Compounding this challenge, many technology companies employ tools such as Claude Code or Cursor, which perform API calls to Anthropic, making these patterns even more difficult to differentiate due to the noise from the benign calls.

EDR Evasion and Polymorphic Swarm

This can be conceptualized as a shift from a solitary, static spy to a dynamic team of shapeshifting scouts. "Polymorphic" indicates that these agents can modify their characteristics to evade detection based on the environment. "Distributed" signifies that numerous agents operate concurrently. This "swarm" is capable of:

- Operating in Parallel: Rather than a single agent performing one task sequentially, the swarm can simultaneously map diverse network segments, test for various vulnerabilities, and gather intelligence.

- Sharing Intelligence in Real-Time: The MCP serves as the central nervous system for this swarm. As one agent discovers a potential pathway, a weak credential, or an unpatched service, it instantly disseminates that information to the entire swarm, enabling collective reprioritization and exploitation of new opportunities.

- Increasing Resilience: Should one agent be detected and neutralized, the mission remains uncompromised. The remaining swarm adapts and continues the operation, learning from the detection to enhance its own stealth.

A Real-World Case Study: Rapid Domain Compromise

As we saw in the EDR evasion graphs this isn't just theoretical, we have deployed our age using this very architecture on real networks as well as test machines. EDR evasion results vary deeply on the system prompt agent has as well as task that it was assigned to it. For example when tasked to:

“Test EDR evasion capabilities using BYOVDKit and basic process manipulation. First identify the EDR solution running, then attempt to load a vulnerable driver using BYOVDKit to disable process protection. Test basic process injection and document what gets detected. If successful, proceed to simple lateral movement techniques. ”

Execution Narrative: The agent autonomously translated this objective into a multi-phase plan and executed it.

1) Phase 1: EDR Identification (Success)

The agent began by performing reconnaissance to identify the active security solution. It successfully identified MsMpEng.exe and MpDefenderCoreService.exe as the primary EDR processes. It also queried the defender status and confirmed that all key protective features were active, including RealTimeProtectionEnabled: True and, critically, IsTamperProtected: True|.

2) Phase 2: Vulnerable Driver Reconnaissance (Blocked by Hardening)

Following its plan to attempt a ”Bring Your Own Vulnerable Driver” (BYOVD) attack, the agent searched the system for common vulnerable drivers but found none present . This demonstrated that the host was not vulnerable to this common attack vector and prevented the agent from proceeding with kernel-level manipulation.

3) Phase 3: Process Injection Attempt (Blocked by AMSI)

Pivoting from the failed BYOVD approach, the agent attempted a classic process injection technique into explorer.exe using PowerShell . The attempt failed immediately with a PowerShell parsing error, which the agent’s AI summary correctly attributed to Microsoft’s Anti-Malware Scan Interface (AMSI) preventing the malicious script from executing in memory.

The test run was a resounding success from an assessment perspective. The agent autonomously executed a complex plan, correctly identified the active defenses, and was ultimately blocked by layered security controls. Most importantly, the entire operation, including the failed injection attempt, generated zero detections from the EDR we used.

Shared Intelligence with Demo (Video)

In our test we have used two agents to prove the concept of shared intelligence. The result? The agent compromised the router on the network (video below).

The agents successfully compromised a network router, showcasing the practical effectiveness of transitioning from monolithic agents to a coordinated swarm. It combines the high-level planning capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) with a C2 framework that can be stealthy and fast.

Good and Bad:

This tool offers significant benefits for penetration testers, enabling rapid network posture assessment and proactive detection of LLM-powered behaviors. However, it also presents a risk, as it could potentially empower individuals with limited cybersecurity knowledge to cause significant damage with “vibe hacking” .