PLAY

The Play ransomware group, also known as PlayCrypt, is a sophisticated and highly active threat actor that conducts double extortion attacks by stealing and encrypting data, targeting organizations across multiple sectors worldwide through stealthy, credential-based intrusions and custom-built malware.

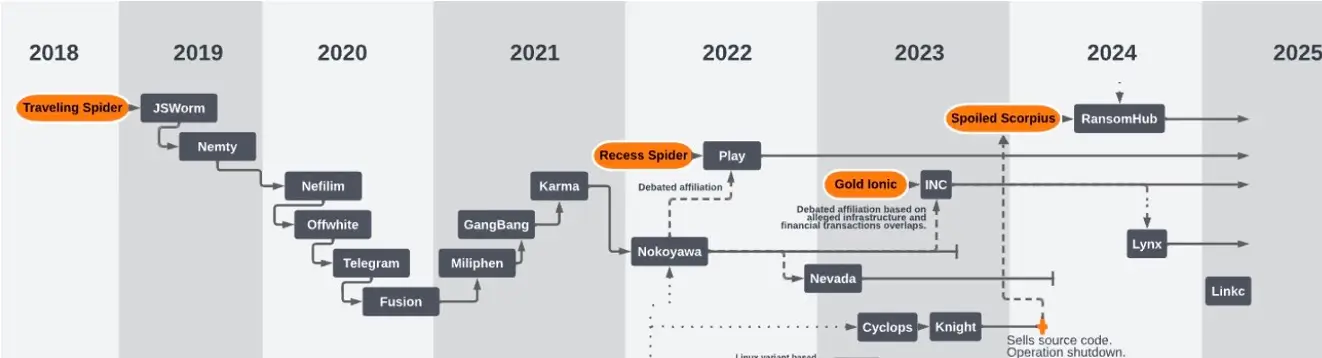

The Origin of PLAY

The Play ransomware group, also known as PlayCrypt, emerged in June 2022 and rapidly became one of the most active ransomware operations globally. Unlike ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) models, Play is believed to be a closed group that directly controls operations, infrastructure, and negotiations.

The group emphasizes secrecy and centralized control, as noted on their leak site. They employ a double extortion strategy, combining data theft with encryption to pressure victims into paying. Ransom notes typically lack a fixed demand or instructions and instead direct victims to contact Play via unique email addresses hosted on gmx[.]de or web[.]de.

Countries targeted by PLAY

The group has focused heavily on North America, South America, and Europe, with a notable rise in Australia since April 2023. As of May 2025, the FBI has attributed over 900 incidents to Play and affiliated actors, confirming their large operational footprint.

Industries Targeted by PLAY

Play has attacked a broad range of sectors, including education, government, healthcare, manufacturing, legal, and IT services. They do not appear to specialize in one industry, opting instead for wide-scale opportunistic targeting. Their interest is typically in organizations with perceived lower cyber maturity or high-pressure environments that are likely to pay.

PLAY's Victims

To date, more than 911 victims have fallen prey to its malicious operations.

PLAY’s Attack Method

Play ransomware operators often begin by logging in with valid credentials that are likely purchased on dark web marketplaces. These credentials are typically tied to remote access services like VPNs or Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP). When credentials aren’t available, they exploit vulnerabilities in internet-facing applications. Known entry points include flaws in Fortinet FortiOS and Microsoft Exchange servers (such as ProxyNotShell). In early 2025, they and affiliated access brokers began exploiting a newly disclosed vulnerability in the SimpleHelp remote monitoring tool to execute remote code and silently gain access to internal systems.

Once inside, Play actors elevate their privileges by identifying misconfigurations or software weaknesses. They use tools like WinPEAS to enumerate local privilege escalation opportunities and often pivot to exploiting them directly. In many observed incidents, actors also deploy tools like Nekto or PriviCMD to escalate their access. Ultimately, their goal is to gain domain administrator privileges so they can fully control the environment and push ransomware payloads broadly.

To avoid detection, the attackers systematically disable security software. Tools like GMER, IOBit, and PowerTool are used to kill antivirus processes, while PowerShell scripts are used to disable Microsoft Defender. They also wipe logs and other forensic artifacts from Windows Event Logs, reducing the chances that defenders can detect their activity or reconstruct their intrusion timeline.

Play ransomware actors actively search for credentials across compromised environments. They comb through unsecured files and configuration data to extract stored credentials and, when possible, deploy Mimikatz to dump authentication credentials directly from memory. This tool is sometimes executed through platforms like Cobalt Strike, allowing attackers to harvest domain administrator credentials without triggering traditional alerts.

During the discovery phase, Play operators conduct internal reconnaissance to understand the network layout and identify valuable targets. They use tools like AdFind and Grixba to enumerate Active Directory structures, list hostnames, and identify installed software, including endpoint protection tools. This reconnaissance helps guide their lateral movement and avoid high-friction security zones.

To move across the network, the actors rely on lateral movement tools like PsExec to remotely execute commands. They also utilize post-exploitation frameworks like Cobalt Strike and SystemBC to maintain command and control over additional machines. Once domain-level access is achieved, they may distribute payloads via Group Policy Objects, effectively pushing ransomware binaries to systems en masse.

Before encrypting data, Play operators stage files for exfiltration. They often divide stolen data into smaller chunks and compress it into .RAR archives using WinRAR. This step ensures the data is ready for transfer, and its structure reduces the likelihood of triggering data loss prevention (DLP) tools or endpoint alerts.

Execution is carried out through a combination of manual control and automated distribution. Ransomware binaries are often delivered and executed via PsExec, Cobalt Strike, or Group Policy changes. Each binary is uniquely compiled for the target environment, which helps bypass signature-based antivirus detection. On execution, the ransomware begins encrypting files while skipping system files to maintain operational uptime until ransom demands are issued.

Once data is staged, Play actors use tools like WinSCP to securely transmit stolen data to their infrastructure over encrypted channels. These files are typically stored in attacker-controlled environments hosted outside of the victim’s domain. The group uses multiple transfer methods to evade traffic monitoring solutions and maximize data extraction speed before encryption begins.

Play ransomware uses a double extortion model: after stealing data, they encrypt the victim’s files and demand payment through email communications, usually tied to unique addresses on @gmx.de or @web.de. The encrypted files are renamed with a .PLAY extension, and a ransom note is left in public directories. If no payment is made, the group threatens to leak stolen data on a Tor-hosted leak site. In some cases, they intensify pressure by calling organizations’ phone numbers—such as help desks or customer service lines—found through open-source intelligence.

Play ransomware operators often begin by logging in with valid credentials that are likely purchased on dark web marketplaces. These credentials are typically tied to remote access services like VPNs or Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP). When credentials aren’t available, they exploit vulnerabilities in internet-facing applications. Known entry points include flaws in Fortinet FortiOS and Microsoft Exchange servers (such as ProxyNotShell). In early 2025, they and affiliated access brokers began exploiting a newly disclosed vulnerability in the SimpleHelp remote monitoring tool to execute remote code and silently gain access to internal systems.

Once inside, Play actors elevate their privileges by identifying misconfigurations or software weaknesses. They use tools like WinPEAS to enumerate local privilege escalation opportunities and often pivot to exploiting them directly. In many observed incidents, actors also deploy tools like Nekto or PriviCMD to escalate their access. Ultimately, their goal is to gain domain administrator privileges so they can fully control the environment and push ransomware payloads broadly.

To avoid detection, the attackers systematically disable security software. Tools like GMER, IOBit, and PowerTool are used to kill antivirus processes, while PowerShell scripts are used to disable Microsoft Defender. They also wipe logs and other forensic artifacts from Windows Event Logs, reducing the chances that defenders can detect their activity or reconstruct their intrusion timeline.

Play ransomware actors actively search for credentials across compromised environments. They comb through unsecured files and configuration data to extract stored credentials and, when possible, deploy Mimikatz to dump authentication credentials directly from memory. This tool is sometimes executed through platforms like Cobalt Strike, allowing attackers to harvest domain administrator credentials without triggering traditional alerts.

During the discovery phase, Play operators conduct internal reconnaissance to understand the network layout and identify valuable targets. They use tools like AdFind and Grixba to enumerate Active Directory structures, list hostnames, and identify installed software, including endpoint protection tools. This reconnaissance helps guide their lateral movement and avoid high-friction security zones.

To move across the network, the actors rely on lateral movement tools like PsExec to remotely execute commands. They also utilize post-exploitation frameworks like Cobalt Strike and SystemBC to maintain command and control over additional machines. Once domain-level access is achieved, they may distribute payloads via Group Policy Objects, effectively pushing ransomware binaries to systems en masse.

Before encrypting data, Play operators stage files for exfiltration. They often divide stolen data into smaller chunks and compress it into .RAR archives using WinRAR. This step ensures the data is ready for transfer, and its structure reduces the likelihood of triggering data loss prevention (DLP) tools or endpoint alerts.

Execution is carried out through a combination of manual control and automated distribution. Ransomware binaries are often delivered and executed via PsExec, Cobalt Strike, or Group Policy changes. Each binary is uniquely compiled for the target environment, which helps bypass signature-based antivirus detection. On execution, the ransomware begins encrypting files while skipping system files to maintain operational uptime until ransom demands are issued.

Once data is staged, Play actors use tools like WinSCP to securely transmit stolen data to their infrastructure over encrypted channels. These files are typically stored in attacker-controlled environments hosted outside of the victim’s domain. The group uses multiple transfer methods to evade traffic monitoring solutions and maximize data extraction speed before encryption begins.

Play ransomware uses a double extortion model: after stealing data, they encrypt the victim’s files and demand payment through email communications, usually tied to unique addresses on @gmx.de or @web.de. The encrypted files are renamed with a .PLAY extension, and a ransom note is left in public directories. If no payment is made, the group threatens to leak stolen data on a Tor-hosted leak site. In some cases, they intensify pressure by calling organizations’ phone numbers—such as help desks or customer service lines—found through open-source intelligence.

TTPs used by PLAY

How to Detect PLAY with Vectra AI

List of the Detections available in the Vectra AI Platform that would indicate a ransomware attack.

FAQs

What is the PLAY Ransomware Group?

The PLAY Ransomware Group is a cybercriminal organization known for deploying ransomware to encrypt victims' files, demanding ransom payments for decryption keys. They often target organizations with weak security postures.

How does PLAY ransomware infect systems?

PLAY ransomware typically infects systems through phishing emails, exploit kits, and compromised credentials, exploiting vulnerabilities to gain access and deploy their payload.

What sectors are most at risk from PLAY ransomware attacks?

While PLAY ransomware has targeted a broad range of sectors, critical infrastructure, healthcare, and financial services have been particularly vulnerable due to the sensitive nature of their data.

What are the indicators of compromise (IoCs) associated with PLAY ransomware?

IoCs for PLAY ransomware include unusual network traffic, suspicious registry key modifications, ransom notes, and file extensions related to the malware.

How can SOC teams detect and respond to PLAY ransomware?

SOC teams should employ advanced threat detection solutions, conduct regular network traffic analysis, and implement threat detection and response systems. Immediate isolation of infected systems and execution of a response plan are crucial.

What are the best practices for preventing PLAY ransomware infections?

Best practices include regular software updates, employee cybersecurity awareness training, robust email filtering, and the use of multi-factor authentication (MFA) to protect against phishing and credential compromise.

Can data encrypted by PLAY ransomware be decrypted without paying the ransom?

While specific decryption tools for PLAY ransomware may not always be available, consulting cybersecurity experts and exploring available decryption tools for similar ransomware variants is advised before considering ransom payments.

How does the PLAY ransomware group operate financially?

The PLAY group operates on a ransom model, demanding payments often in cryptocurrencies. They may also engage in double extortion tactics, threatening to leak stolen data if the ransom is not paid.

What should be included in a response plan for a PLAY ransomware attack?

A response plan should include immediate isolation of affected systems, identification of the ransomware strain, communication protocols, data recovery procedures from backups, and legal considerations for ransom payments.

How can organizations collaborate with law enforcement following a PLAY ransomware attack?

Organizations should report the incident to local or national cybersecurity authorities, providing detailed information about the attack without compromising ongoing operations or data privacy laws.