What Is a Botnet? How Attackers Exploit Malware

Key insights

- Mirai remains one of the most active IoT botnets in 2025 (Kaspersky)

- Mirai-derived IoT botnets exceed 40,000 active bots daily (Foresiet)

- IoT botnets power record-breaking DDoS attacks over 31 Tbps (Tom’s Hardware)

Once a device is part of a botnet, it can be remotely controlled by an attacker known as a bot herder who issues commands to launch DDoS attacks, steal credentials, and spread malware — often without the owner's knowledge. These networks can range from hundreds to millions of infected devices, allowing cybercriminals to scale their operations with minimal effort.

Bot vs. botnet vs. zombie computer

A bot is a single device infected with malicious software that allows remote control. A botnet is a coordinated network of these infected devices working together under the control of an attacker, often called a bot herder or botmaster.

The term zombie computer (sometimes called a zombie device) refers to a bot that is actively receiving commands and performing malicious actions, usually without the owner’s awareness. In practice, most modern botnets include a mix of personal computers, servers, mobile devices, and Internet of Things (IoT) systems.

How do botnets work across modern networks?

Botnets work by turning everyday devices into remotely controlled tools that act in coordination. While individual bots may generate little activity on their own, the combined behavior of thousands or millions of infected systems allows attackers to carry out large-scale attacks efficiently and quietly.

Botnets test cyber resilience by coordinating low-signal activity at scale. An AI-driven NDR platform for cyber resilience helps teams detect that coordination and stop attacks early.

Botnets follow a three-stage lifecycle: infection, command and control, and exploitation.

1. Infection: How devices become bots

Cybercriminals use various techniques to compromise systems and expand their botnet:

- Phishing Emails – Malicious attachments or links install botnet malware.

- Software Vulnerability Exploits – Hackers target unpatched operating systems, applications, and IoT devices.

- Drive-By Downloads – Malware is installed when users visit infected websites.

- Brute-Force Attacks – Automated tools guess weak passwords to gain system access.

Once compromised, a device rarely shows immediate signs of infection. Botnet malware is designed to persist quietly, often installing additional components over time. In enterprise environments, a single infected endpoint can also become a launch point for credential harvesting or lateral movement, accelerating botnet growth.

2. Command and Control (C2) Systems

Command and control is what turns isolated infections into a coordinated botnet. Through C2 infrastructure, attackers can issue instructions, update malware, and retrieve stolen data at scale. Even when communications are encrypted, C2 activity often follows patterns that can stand out in network traffic.

After infection, bots connect to a command-and-control (C2) server, where attackers issue commands and collect stolen data. The two main C2 structures include:

- Client-Server Model – Bots connect to a centralized C2 server, making management efficient but vulnerable to takedown efforts.

- Peer-to-peer (P2P) Model – Bots communicate with each other rather than a central server, making the botnet more difficult to disrupt.

From a defensive standpoint, botnet C2 traffic often appears as repeated outbound connections, unusual DNS behavior, or communication with destinations rarely contacted by other devices in the environment. These patterns are especially telling when they originate from systems that typically should not initiate external connections.

3. Exploitation: How Attackers Use Botnets

Once established, botnets are used for a range of cybercriminal activities:

- DDoS Attacks – Overload websites or networks with traffic to shut them down

- Credential Theft – Logging keystrokes or stealing saved passwords for financial fraud

- Cryptojacking – Using infected devices to mine cryptocurrency without the owner’s consent

- Click Fraud – Generating fake ad clicks to steal revenue from advertisers

- Spam and Phishing Campaigns – Sending mass phishing emails to expand infections

Types of botnets

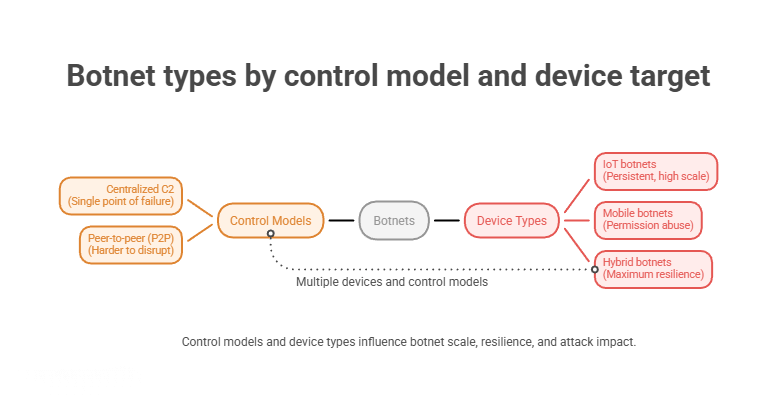

Botnets are commonly categorized by how they are controlled and which devices they target. These differences directly influence how botnets scale, how resilient they are to disruption, and what types of attacks they are best suited to carry out.

Some botnets use centralized command-and-control, where infected devices check in with a single server for instructions. This model is efficient but fragile, as disrupting the control infrastructure can significantly weaken or disable the botnet.

→ See how Vectra AI detects encrypted C2 traffic by identifying covert channels used by modern botnets.

Other botnets use peer-to-peer control, allowing infected devices to relay commands among themselves. By removing a central point of failure, P2P botnets are harder to disrupt and can persist longer.

The types of devices recruited into a botnet further shape its behavior and impact. IoT botnets often draw from routers, cameras, and embedded systems that lack strong authentication or regular patching. Mobile botnets spread through malicious apps and abused permissions. Hybrid botnets combine multiple control models and device types to maximize scale, redundancy, and survivability.

These design choices are not abstract. They determine what botnets are used for, how large they can grow, and why certain attack types, such as distributed denial-of-service, remain so difficult to stop.

Botnet DDoS attacks

A botnet DDoS attack uses a large number of compromised devices to overwhelm a target with traffic, exhausting bandwidth, compute resources, or application capacity. Individually, each bot may generate only modest traffic. Together, they can disrupt services at scale.

Botnet-driven DDoS attacks are difficult to mitigate because traffic often originates from legitimate devices with real IP addresses. This makes simple IP blocking ineffective. Modern attacks frequently combine volumetric floods with application-layer requests, allowing attackers to adapt as defenders attempt to filter traffic.

Because these attacks rely on coordination rather than malware execution on the target, early detection depends on identifying abnormal traffic patterns across the network rather than single-device behavior.

→ Learn how denial-of-service (DoS) attacks are detected in modern networks.

IoT Botnets

An IoT botnet is formed from compromised Internet of Things devices such as routers, cameras, sensors, and other embedded systems. These devices are attractive targets because they often lack strong authentication, receive infrequent updates, and remain online continuously.

Many devices are deployed with default credentials or exposed services, allowing automated scanning and infection. Once compromised, these systems may remain part of a botnet for long periods.

IoT botnets are commonly used for DDoS attacks, but they can also support scanning, proxying traffic, or distributing malware. Their persistence and scale make them especially difficult to eradicate.

What is the Mirai botnet, and how do IoT botnets scale?

The Mirai botnet is one of the most well-known IoT botnets and helped define how attackers exploit insecure embedded devices at scale. Mirai primarily targeted routers, cameras, and other IoT systems by scanning for exposed services and logging in using default or hardcoded credentials.

Once infected, devices were enrolled into a centralized command-and-control infrastructure and used to launch large-scale DDoS attacks against high-profile targets. Mirai demonstrated that even low-power devices could generate significant impact when coordinated.

Mirai remains one of the most active IoT botnet threats in 2025, exploiting weak credentials and unpatched firmware to coordinate large groups of infected devices. Recent research shows Mirai-derived variants with more than 40,000 active bots per day, highlighting persistent evolution and ongoing exploitation.

Large IoT botnets like Aisuru/Kimwolf have powered record-setting DDoS attacks exceeding 31 Tbps, illustrating how compromised devices can be leveraged for massive traffic-based disruption

The lifecycle of a botnet: From creation to takedown

Botnets don’t emerge overnight—they follow a lifecycle that enables them to grow, operate, and sometimes evade takedown attempts.

1. Creation and Deployment

- Cybercriminals develop or purchase botnet malware on dark web marketplaces.

- The malware is embedded in phishing emails, malicious ads, or exploit kits.

2. Recruitment and Growth

- Users unknowingly download malware, turning their devices into bots.

- The botnet spreads through self-propagating techniques like worm-like replication.

3. Exploitation and Monetization

- Attackers use infected devices for DDoS attacks, spam campaigns, data theft, and cryptojacking.

- Some botnets are rented out as Botnet-as-a-Service (BaaS) for profit.

4. Detection and Law Enforcement Response

- Security researchers and law enforcement track C2 servers, bot activity, and malware signatures.

- Attempts are made to disrupt botnet operations by blocking command channels.

5. Takedown Attempts and Resurgence

- Authorities seize botnet infrastructure and domains to cut off attacker control.

- Cybercriminals quickly rebuild botnets using new infrastructure and malware variants.

Despite takedown efforts, botnets often resurface in new forms, evolving to evade detection and exploit emerging vulnerabilities.

How botnets stay undetected: Advanced evasion techniques

Modern botnets use sophisticated techniques to remain invisible to security tools. These techniques make them harder to detect and remove.

1. Encryption and Obfuscation

- Botnets encrypt C2 communications to hide traffic from security tools.

- Some use domain fluxing, which rapidly changes their C2 server locations.

2. Fileless Malware

- Some botnets run entirely in memory, leaving no files on disk for antivirus programs to detect.

3. Fast-Flux Networks

- Bots frequently switch IP addresses, making it difficult for security teams to block C2 traffic.

4. Sleeping Botnets

- Some bots remain dormant for long periods before activating, evading detection.

5. Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Communication

- Decentralized botnets avoid using a single C2 server, making takedowns much harder.

These evasion techniques make botnets a persistent cybersecurity threat.

Botnet traffic: what defenders look for

Botnet activity is rarely loud at the individual endpoint level. Instead, it appears as small, repeated behaviors that blend into normal traffic unless viewed in context.

One common signal is beaconing, where an endpoint repeatedly initiates outbound connections at regular intervals. These connections often lead to destinations that are uncommon across the rest of the environment. Unusual DNS behavior is another indicator, including repeated failed lookups or rapid changes in domains as attackers rotate infrastructure.

Endpoint behavior also matters. Devices that suddenly begin initiating external connections, consuming abnormal CPU resources, or generating outbound traffic inconsistent with their role may indicate botnet participation. When these endpoint signals align with network patterns, they provide strong evidence of coordinated botnet activity.

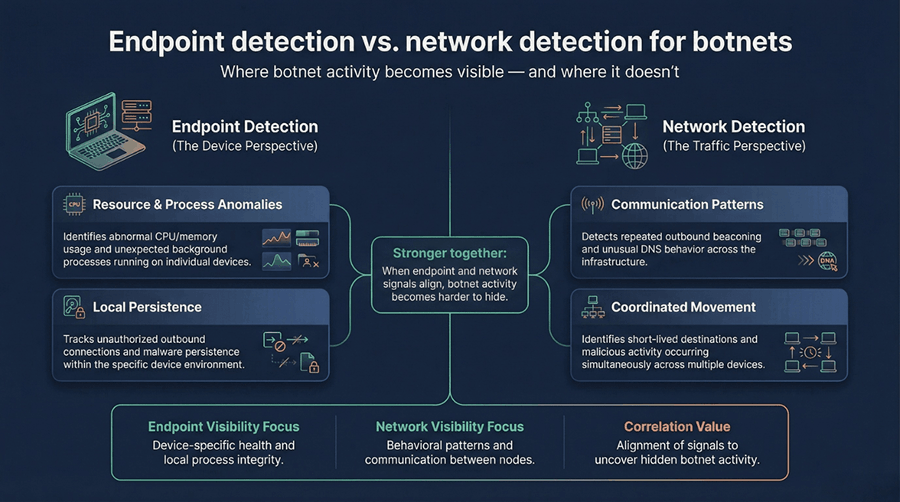

Endpoint detection vs. network detection for botnets

Botnet activity can surface at both the endpoint and the network layer, but each provides a different piece of the picture. Endpoint signals often show local impact, while network signals reveal coordination and scale.

At the endpoint level, botnet infections may appear as abnormal resource usage, unexpected background processes, or unauthorized outbound connections initiated by the device. These indicators can suggest compromise but may be subtle when viewed in isolation.

At the network level, botnets are easier to spot as collective behavior. Repeated outbound connections, unusual DNS activity, and communication with rare or short-lived destinations can reveal coordinated control. When endpoint and network signals align, defenders gain higher confidence that a device is participating in a botnet rather than experiencing a one-off anomaly.

How to identify if your device is part of a botnet

Many users don’t realize their devices are infected. Here are the top warning signs to look for:

1. Unusual Network Activity

- Unexpected spikes in outgoing data traffic could mean your device is communicating with a C2 server.

2. Slow Device Performance

- If your computer, phone, or IoT device is sluggish for no reason, it may be running hidden botnet operations like cryptojacking.

3. Frequent Captchas on Websites

- If you constantly see captchas while browsing, your IP may be flagged for suspicious botnet activity.

4. Unexpected Outgoing Emails or Messages

- A botnet might be using your device to send spam or phishing messages to others.

5. Connections to Suspicious IPs

- Your firewall or network monitoring tools may detect connections to known botnet-related domains.

How bot herders control malware

A bot herder is the cybercriminal managing the botnet, ensuring it remains operational and profitable while avoiding detection.

Command and Control Mechanisms

Bot herders maintain control through C2 infrastructure, which allows them to:

- Send attack commands to infected bots.

- Distribute malware updates to enhance functionality.

- Collect stolen data and relay it to criminal networks.

To avoid detection, many botnets use encryption, domain-fluxing (rapid domain changes), and fast-flux DNS techniques to keep C2 infrastructure hidden.

Evasion and Persistence Techniques

Bot herders use advanced methods to ensure continued operation, including:

- Polymorphic Malware – Constantly changing code to bypass antivirus detection.

- Encrypted C2 Communication – Masking commands to avoid security tools.

- P2P Networks – Preventing centralized takedowns by distributing control across multiple infected machines.

What is botnet-as-a-service, and how do attackers use it?

Botnet-as-a-service (BaaS) allows cybercriminals to rent access to infected endpoints rather than building and maintaining their own botnets. Buyers can pay for botnet capacity to launch DDoS attacks, distribute spam, harvest credentials, or deliver additional malware.

This model lowers the barrier to entry and increases attack volume. Because rented botnets can be spun up quickly and discarded just as fast, defenders often see high churn in infrastructure and malware variants. Even when a campaign is disrupted, infected endpoints and stolen credentials can enable new operators to reuse the same devices for future attacks.

AI botnets and automation: what’s real and what’s misunderstood

Searches for “AI botnets” often reflect growing concern about automation rather than a distinct new category of malware. Most botnets already rely on automated processes to scan for vulnerabilities, spread infections, and execute attacks at scale.

What’s changing is efficiency. Attackers increasingly automate decisions such as which devices to target, when to activate bots, and how to rotate infrastructure to evade disruption. At the same time, defenders use behavioral analysis and machine-assisted detection to identify subtle botnet patterns that would otherwise blend into normal activity.

In practice, the challenge is not artificial intelligence itself, but speed and scale. Botnets move faster and change more frequently, which makes visibility and correlation across endpoints, networks, and cloud environments more critical than ever.

See how Vectra AI detects botnet activity by identifying automated behaviors that signal coordinated compromise at scale.

How Attackers Profit from Botnets

Botnets generate revenue in several ways:

- Selling Access ("Botnet-as-a-Service") – Renting infected devices to cybercriminals

- Ransomware Deployment – Encrypting victim files and demanding payment

- Financial Fraud – Stealing banking credentials and executing unauthorized transactions

- Cryptocurrency Mining – Using infected devices to generate cryptocurrency for attackers

Active botnets

While some botnets have been dismantled, many continue to evolve and pose threats today. Recent examples include:

Dridex – A Persistent Banking Trojan

Dridex spreads via phishing emails and is used for financial fraud, credential theft, and ransomware deployment. It continuously adapts, making it difficult to detect and remove.

Emotet – A Resilient Malware Distributor

Emotet is one of the most advanced malware delivery botnets, distributing ransomware and credential stealers. Despite takedown attempts, it frequently resurfaces with improved capabilities.

Mirai – The Leading IoT Botnet

Mirai infects IoT devices with weak passwords, turning them into tools for large-scale DDoS attacks. Numerous variants continue to target routers, cameras, and smart home devices.

Gorilla – An Emerging Cloud and IoT Threat

Gorilla is a recently identified botnet that has launched hundreds of thousands of DDoS attack commands worldwide, focusing on cloud-based infrastructure and IoT devices.

Necurs – A Dormant but Dangerous Threat

Necurs is a modular botnet used for spam campaigns, financial fraud, and malware distribution. It has been linked to banking trojans like Dridex and Locky ransomware. While it has remained relatively inactive in recent years, it has the potential to resurface.

Mantis – The Next-Generation DDoS Botnet

First discovered in 2022, Mantis is a highly efficient botnet capable of launching record-breaking DDoS attacks with fewer infected machines than previous botnets. It uses advanced techniques to amplify attack traffic, making it a major threat to businesses and cloud infrastructure.

Notable Disabled Botnets

While inactive, the following botnets shaped modern cyber threats:

- ZeuS (Zbot) – A banking trojan responsible for millions in financial fraud

- GameOver Zeus – A resilient, decentralized version of ZeuS

- Cutwail – A spam botnet that sent billions of fraudulent emails

- Storm – One of the first dark web rental botnets

- ZeroAccess – A botnet used for click fraud and cryptojacking

- 3ve – A sophisticated ad fraud botnet that cost advertisers millions of dollars

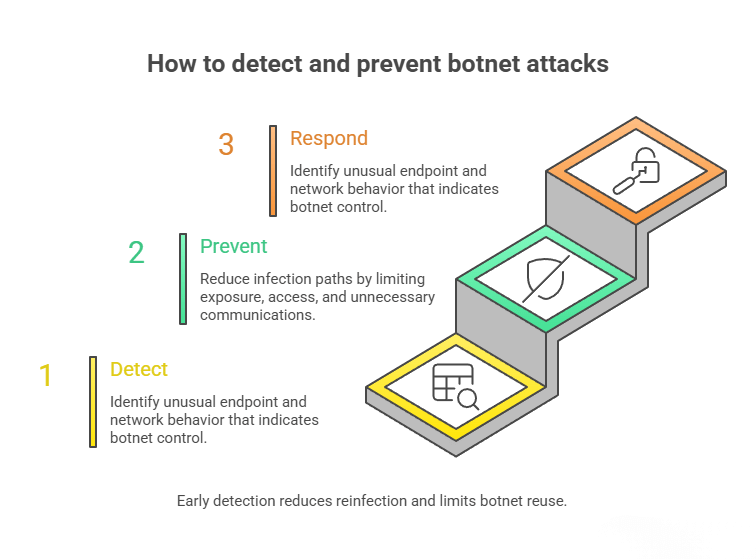

How to detect and prevent botnet attacks

Detecting and preventing botnet attacks requires visibility into both device behavior and network activity. Because botnets are designed to operate quietly, early detection often depends on identifying small anomalies that become meaningful when viewed together.

Because botnet infrastructure changes frequently, prevention should not rely solely on static blocklists. Behavioral monitoring and threat intelligence help identify emerging command-and-control patterns, allowing security teams to disrupt botnet activity before it escalates into larger attacks or secondary compromise.

Preventing and responding to botnet activity requires clear, practical steps:

- Keep Software Updated – Regularly patch operating systems, applications, and IoT devices.

- Use Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) – Prevent credential stuffing attacks.

- Deploy Network Segmentation – Restrict infected systems from communicating laterally.

- Monitor Threat Intelligence Feeds – Block known botnet domains.

- Implement AI-Powered Security – Use behavior-based detection to spot botnet activity.

How to Remove a Botnet Infection

If you believe a device may be part of a botnet, the priority is containment and validation rather than immediate cleanup. Botnet infections often persist because systems remain connected to command-and-control infrastructure or because attackers retain access through stolen credentials.

If a botnet is detected:

- Isolate the Infected System – Disconnect it from the network to prevent spread.

- Block C2 Communications – Prevent outbound connections to botnet servers.

- Use Advanced Threat Detection – AI-driven tools can identify and eliminate malware.

- Reset Compromised Credentials – Change passwords and enforce security policies.

Addressing botnet activity early helps prevent reinfection and reduces the risk of compromised endpoints being reused in future campaigns.

See how Vectra AI detects real attacks by exploring an interactive tour of how attacker behaviors are identified before breaches occur.

Related cybersecurity fundamentals

FAQs

What is a botnet?

A botnet is a network of internet-connected devices that have been infected with malware, allowing a remote attacker to control them. These compromised devices, known as "bots," can include computers, mobile devices, and IoT devices.

How do botnets spread?

Botnets spread through various methods, including phishing emails, exploiting vulnerabilities in software or devices, drive-by downloads, and through the use of malicious websites. Once a device is compromised, it can be used to infect other devices, expanding the botnet.

What are common uses of botnets by cybercriminals?

Common uses include launching DDoS attacks to overwhelm and take down websites or networks, distributing spam emails, executing click fraud campaigns, stealing personal and financial information, and deploying ransomware.

How can organizations detect the presence of a botnet?

Detection methods include monitoring network traffic for unusual activity, analyzing logs for signs of compromise, employing intrusion detection systems (IDS), and using antivirus and antimalware solutions to identify malicious software.

What strategies are effective in preventing botnet infections?

Effective prevention strategies encompass: Implementing robust security measures such as firewalls, antivirus programs, and email filters. Regularly updating and patching software and operating systems to close vulnerabilities. Educating employees about the risks of phishing and malicious downloads. Segmenting networks to limit the spread of infections. Employing network behavioral analysis to detect anomalies.

What is the difference between a bot, a botnet, and a zombie computer?

A bot is a single device infected with malware that allows it to be remotely controlled. A botnet is a coordinated network of many such infected devices working together under the control of an attacker, often called a bot herder. A zombie computer refers to a bot that is actively receiving commands and performing malicious actions without the owner’s awareness. In practice, modern botnets often include a mix of computers, servers, mobile devices, and IoT systems.

What does botnet traffic look like on a network?

Botnet traffic typically appears as small, repeated behaviors rather than large spikes. Common indicators include regular outbound “beaconing” connections, unusual DNS activity, and communication with destinations rarely contacted by other devices in the environment. Because botnet traffic is often encrypted and low-volume, it can blend into normal activity. Correlating these network patterns with endpoint behavior helps distinguish botnet activity from benign anomalies.

How do botnets communicate with command-and-control (C2) servers?

Botnets communicate with command-and-control (C2) infrastructure to receive instructions, update malware, and send stolen data. This communication may use centralized servers, peer-to-peer networks, or hybrid models. To evade detection, attackers often encrypt C2 traffic and rotate domains or infrastructure frequently. Even so, C2 activity often follows recognizable patterns, such as repeated outbound connections, unusual DNS lookups, or traffic to short-lived or uncommon destinations.

What is botnet-as-a-service (BaaS)?

Botnet-as-a-service (BaaS) is a model in which cybercriminals rent access to infected devices instead of building their own botnets. Buyers can use rented botnets to launch DDoS attacks, distribute spam, harvest credentials, or deliver malware. This model lowers the barrier to entry and increases attack volume, as botnets can be quickly reused or repurposed. Even after takedowns, infected endpoints may be reused by new operators.

What are the signs that a device is part of a botnet?

Signs that a device may be part of a botnet include unexplained slowdowns, abnormal CPU or network usage, and unexpected background processes. On a network, indicators may include repeated outbound connections, unusual DNS behavior, or communication with suspicious destinations. In some cases, compromised devices may send spam or trigger account lockouts due to credential abuse. No single sign confirms infection, but correlated signals strongly suggest botnet activity.